THE CENTER FOR POPULAR MUSIC AT

MIDDLE TENNESSEE STATE UNIVERSITY:

DOCUMENTING THE BROAD RANGE OF

AMERICAN VERNACULAR MUSIC

BY PAUL F. WELLS

HISTORY

The Center for Popular Music at Middle Tennessee

State University (MTSU) was established in 1985 as one of the "Centers

of Excellence" in Tennessee's public university system. The aim of

the Centers program was to create institutes that would foster advanced

research and scholarship in fields in which the various schools had existing

strengths. MTSU’s location in Murfreesboro, thirty-five miles from

Nashville, makes it a logical choice for a center related to popular-music

scholarship. The university’s Department of Recording Industry offers

a successful music-business training program; in fall 1997, the department

had an enrollment of approximately thirteen hundred majors. The MTSU

Department of Music offers a bachelor’s degree with emphasis in the music

industry, and several members of the MTSU faculty—notably Charles Wolfe

in the English Department—engage in scholarship related to popular music.

Another important factor is the prominent role that Tennessee has played

in the history and development of virtually all genres of popular music

in the twentieth century, making the state a marvelous laboratory in which

to study popular music.

An interdisciplinary committee drawn from

the departments of Recording Industry, English, Music, History, and Speech

and Theater, and headed by the dean of the College of Liberal Arts, drew

up the proposal for a "Center of Excellence in Music Archives and Research"

in 1985. The Tennessee Higher Education Commission approved the proposal

in April 1985, and the Center officially came into being on 1 July 1985.

The committee that created the proposal served as the search committee

for the Center's first director. I was offered the position in September

1985 and began work in November.

When I first learned about the plans to create

a new research center for popular music, I realized that this represented

an extraordinary opportunity for someone to build an archive and program

from the ground up. Just how true this was became abundantly clear

when I reported for work to an empty office. The first several months

were devoted to such essential tasks as establishing an administrative

office, hiring a secretary, and laying the foundations for the Center’s

physical and intellectual development.

The committee that first drafted the proposal

and then conducted the search for a director assumed a final incarnation

as a faculty advisory board. Because of its interdisciplinary nature,

the Center is not part of any of the five undergraduate colleges at MTSU,

and the director of the Center reports directly to the Provost and Vice

President for Academic Affairs. The board functions as a peer advisory

panel that includes representation from various campus factions.

I met with them frequently in the early days, and the members provided

sound guidance, especially in matters of university policy. They

did not dictate details of the Center’s day-to-day operations, but rather

allowed me considerable flexibility in shaping all aspects of the collections

and programs. Their one clear mandate was that the Center should

establish a large archive to serve as a major resource for the region.

The board also agreed to my suggested name for the new enterprise: the

Center for Popular Music.

The first home of the Center was in MTSU’s

Learning Resources Center (LRC). The collection was assigned space

in what was originally the Environmental Simulation Laboratory, a large

cylindrical structure—approximately thirty feet in diameter by thirty feet

in height—attached to one end of the LRC; Center staff referred to it,

with mock affection, as "the silo." The laboratory was a type of

multimedia theater in which various environmental conditions supposedly

could be replicated, but the capability of the facility had never been

fully utilized. Plans for converting this space to an archive and

library were drawn up with the help of Michael Sniderman, the set designer

for the Speech and Theater Department. Center funds could not be

used to cover the costs of renovation, so extra money had to be sought

from the university president. He rejected our first proposal, which

would have divided the silo’s vertical space into two floors, so we devised

a contingency plan that used only the ground floor. Plans were in

the works for a new building that would house both the College of Mass

Communication and the Center, and we were hopeful that these would become

reality before we outgrew the space in the LRC.

COLLECTION DEVELOPMENT

In the meantime, we needed to expend the funds

that had been designated to establish the collection. We began with

the purchase of new books, in-print LPs, and current periodicals, and developed

a network of dealers in used books and sound recordings. A trip to

the 1986 Music Library Association meeting in Milwaukee was productive

in establishing contacts within the field that led to the identification

of available materials. I learned at the meeting that Brigham Young

University wished to sell duplicate holdings of approximately five thousand

pieces of mid-nineteenth-century sheet music. I also met Victor Cardell,

who had just been hired by the University of California, Los Angeles, as

archivist for their Archive of Popular American Music, a vast sheet-music

collection of over one-half million items that included several thousand

duplicates. I then learned that Ray Avery, a Los Angeles collector

and dealer who specialized in jazz and other forms of African American

music, was interested in selling much of his personal collection, which

included sheet music, records, photographs, various bits of music ephemera

and memorabilia, and manuscript collections related to Ferde Grofé,

Paul Whiteman, Johnny Mercer, and others. A trip to Los Angeles and

Provo in spring 1986 to inspect these collections ultimately led to the

purchase of the BYU sheet music, the Avery materials, and approximately

twenty-five thousand pieces of sheet music from UCLA, although over a year

passed before all the transactions were completed. The collection

of the Center for Popular Music now had cornerstones on which to build.

The wide variety of materials included in

these early acquisitions forced the issue of defining the parameters of

our collection. What genres would we collect? What media?

What would be the chronological scope? How tightly would we define

"popular music"? It would be misleading to say that these questions

were answered by a process of intensive, focused deliberation that resulted

in a finely tuned collection-development policy. Rather, solutions

evolved over time as I extended my own knowledge of American popular music

and the materials that document its development.

Both my perspective as a folklorist and my

research in early country ("hillbilly") music and blues had made me keenly

aware that interplay between oral and commercial traditions is a historical

constant, and that one must understand popular traditions in order fully

to comprehend folk traditions—and vice versa. Traditional singers,

for example, often perform songs that can be traced to nineteenth-century

sheet music, broadsides, or songsters. Country fiddlers and guitar

players commonly learn tunes from recordings as well as from other musicians

in their communities. Conversely, the recording companies in the

1920s transformed local folk-music traditions of black and white rural

southerners and northern urban ethnic communities into important, mass-marketed

segments of the music industry.

|

|

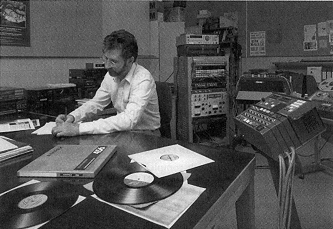

A selection of items from the collection of the Center for Popular Music. All materials in this grouping are products of Tennessee's music business, and all document the variety of the state's most important cultural product. (Courtesy of MTSU Photographic Services.) |

Similarly, research that I had done at the John Edwards Memorial Foundation (JEMF) at UCLA on the history of songs recorded by traditional country artists—such as the Carter Family and the Blue Sky Boys—made me acutely aware of the limitations of genre-based and media-based research collections. The JEMF has a wonderful collection of pre-World War II 78-rpm recordings of hillbilly music and excellent holdings of country-song folios, but relatively little of the collection is pertinent to the study of songs that are derived from Tin Pan Alley and earlier eras of mainstream popular song or that are rooted in various forms of vernacular religious music. For research into this material, I was forced to turn to other resources at UCLA to find sheet music, songsters, and shape-note hymnals. This entailed expending considerable time and energy traipsing from one collection to another, and access to some materials was often difficult, impossible, or denied.

It seemed that the situation called for a more inclusive and integrated approach—a popular-music research collection that would cut across genre lines, that would encompass all media in which music has been fixed and sold, and that would have considerable historical depth. It was also important to remember that scholars from a variety of disciplinary approaches would be making use of the Center’s resources. An essential step was to establish an intellectual underpinning to guide the development of not only the collections, but also future research projects, publications, and public programs.

What has evolved is a conceptual framework that draws in more or less equal measure from folklore, ethnomusicology, historical musicology, and communications. From folklore comes a recognition of the importance of the relationship between folk and commercial traditions. From ethnomusicology comes an awareness of the need to look at music in the context of the culture in which it thrives. From historical musicology comes the recognition that popular music is not confined to contemporary styles, but rather that popular music of one form or another has always occupied a significant place in American cultural history. To understand fully any genre of popular music, one must study it through time and alongside the other forms of music with which it coexists. From communications comes the recognition that popular music must be studied within the framework of the commercial and technological factors that shape its development.

Given all this, the pragmatic consideration of the scope of the collection remained a problem. In the best of all possible worlds, the ideal popular-music archive would possess one copy of every piece of sheet music, every song book, and every sound recording ever issued—something that would be neither possible nor practical, so limitations had to be devised while maintaining a sense of the overall picture of American popular music.

|

Partly because of my own increasing curiosity

about the early development of today’s musical forms, I found the opportunity

to build a collection that would include pre-twentieth-century material

particularly appealing. The history of popular music in America did

not begin with the Beatles, Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, Jelly Roll Morton,

Scott Joplin, or even Stephen Foster. Americans have always sung,

danced, and otherwise "consumed" music, and to set some arbitrary chronological

starting point for the collection seemed highly artificial. Thus,

we take as our beginning the introduction of European and African peoples

to North America.

The Center’s location in the Southeast made

it logical to build a collection that would reflect a southern perspective

on the history of popular music. This raised a bit of a problem,

however, in that excellent repositories devoted specifically to blues,

country music, and jazz already existed, and it seemed foolish for the

Center to collect these genres in depth. What we needed for these

areas was a solid, representative collection that would serve curricular

needs—a study-level collection rather than a research-level collection—and

a selective gathering of items relevant to cross-genre study. Although

rock was—and is—well served by the collections at Bowling Green State University,

there was no comparable resource in the Southeast. Rock and its roots

thus became a genre focus of the Center’s work.

Similarly, we felt that the long-standing relationship between secular

popular music and the variety of forms of vernacular religious music—music

of a sacred theme normally performed outside of formal religious services—had

not been fully recognized by other popular-music repositories. This

led to a decision to embrace a broad range of genres, including shape-note

hymnody, Negro spirituals, southern gospel, African-American gospel quartets,

contemporary Christian music, and heavy-metal Christian rock.

COLLECTIONS

What, then, within this fairly complex framework,

has the Center collected in the past twelve years? As of 31 December

1997, the collection consisted of approximately 14,600 books, including

nearly 7,000 special-collections items; 96,000 sound recordings in formats

from cylinders to compact discs; 56,000 pieces of sheet music, including

3,500 song broadsides; nearly 110 linear feet of manuscripts; 7,700 photographs

and other iconographic items; over fifty linear feet of clipping files,

and sizable holdings of playbills, trade catalogs, and microforms.

The Center currently subscribes to over 400 periodical titles, and has

partial backruns of an additional 1,100 titles.

Not included in these totals are materials

acquired in July 1997 from Brad McCuen, a music business executive best

known for his long tenure with RCA Victor. The McCuen collection

includes over 25,000 sound recordings, significant quantities of sheet

music, periodicals, and books, and—perhaps most important—business records,

files, and correspondence that document his career and contributions to

the music industry. His sound-recordings collection is particularly

strong in jazz and also includes much show music and rock and roll.

Bare numbers are of little meaning in actually conveying a sense of

the collection, so it will perhaps be useful to describe some highlights

of the Center’s resources.

Sheet Music

The Center’s sheet-music collection is thought to be the largest in

the Southeast. Holdings grew quickly in the Center’s early years,

but we are now quite selective in adding items, with a focus on qualitative,

rather than quantitative, growth. The collection is divided more

or less evenly between large- and small-format items. Since the 1920s,

sound recordings have been the primary means by which popular songs are

fixed and sold, so we are more concerned with collecting sound recordings

than sheet music for the modern era. Current growth of the sheet-music

collection, therefore, is focused primarily on pre-twentieth-century material.

More than 100 items in the collection have been identified as pre-1800

imprints and more than 750 as 1801-25 imprints.

|

Southern imprints and songs with southern imagery are of particular interest to us. Songs from the blackface minstrelsy tradition are especially sought after, as are songs that reflect movements, events, and issues in social and political history—such as wars, political campaigns, reform movements, and inventions. Rags, blues, and early jazz items are also welcome, as are songs by African-American songwriters and by women. Musical theater is well represented, largely through the materials acquired from UCLA.

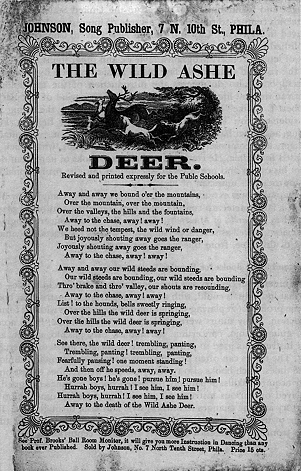

Kenneth S. Goldstein Collection of American Songsters and Song Broadsides

In the last ten years of his life, folklorist Kenneth S. Goldstein (1927–1995) assembled impressive collections of song broadsides and pocket songsters, dating primarily from the nineteenth century. Goldstein had become convinced of the importance of broadsides and songsters as the source and means of transmission for many of the songs in the repertories of the traditional folksingers with whom he worked. His personal collection of these items grew quickly to become perhaps the largest such private collection in the country, comprising approximately thirty-three hundred broadsides and fifteen hundred songsters. The Center acquired Goldstein’s broadsides in 1994 and the songsters in 1996, shortly after his death in November 1995. These are perhaps the most important individual collections owned by the Center. The broadside collection is, to our knowledge, the only sizable collection of broadsides in the South and is comparable to those of the larger, older libraries in the Northeast. The Goldstein songster collection was recently described as "the preeminent songster collection in the U.S."

Alfred Moffat Collection

The oldest materials in the Center’s collection were a part of the personal library of Scottish scholar Alfred E. Moffat (1863-1950) and formerly owned by the Forbes Library in Northampton, Massachusetts. Moffat compiled and edited numerous books of music from eighteenth-century Britain and Ireland; the eighty-five volumes acquired by the Center formed a sizable portion of Moffat’s working collection of source material. Included are several volumes of fiddle tunes compiled by the great Scottish fiddlers and composers Niel and Nathaniel Gow and William Marshall, numerous collections of Scots songs, a rare guitar tutor published by Robert Bremner, many song anthologies, and copies of various musical miscellanies and magazines.

Documents of Professional Musicians

The Center has been fortunate to acquire scrapbooks,

correspondence, and other ephemera and memorabilia from a variety of professional

musicians. Ruperto Marco Aurelio Chacon was a Chilean-born guitarist

and mandolinist who moved to the United States in the late nineteenth century

to capitalize on a surge of interest in the mandolin. He lived in

New York City and later in New Haven, Connecticut, and established himself

as a teacher and performer. He compiled a scrapbook of letters, concert

programs, reviews, and other items that chronicles the rise and ultimate

decline of his musical career. By extension, the scrapbook also documents

the introduction of the mandolin to American musical life and the decline

of its first period of popularity.

|

Robert E. "Mike" Doty enjoyed a long career

during the Swing Era as a sideman with Tommy Dorsey, Ray Noble, Bunny Berigan,

Fred Waring, and other band and orchestra leaders. A multi-instrumentalist,

arranger, and composer, Doty also led his own band, with which he recorded

for a time. He compiled several scrapbooks of items that document

his career and provide valuable insight into the professional life of a

journeyman musician of his era.

Perhaps the most extraordinary scrapbook is

the one compiled by Billy Carter, a late-nineteenth-century blackface comedian

and banjo player profiled in Monarchs of Minstrelsy. Carter

also saved concert programs and reviews as well as several personal-appearance

contracts. Documentation of this type, from this era, is extremely

rare.

Tutors and Tune Books for Popular Instruments

The nineteenth century saw the rise of autodidacticism in music—the idea that individuals could, with a bit of help from an instruction book, become proficient at playing various musical instruments without formal instruction. Many tutors were published for violin/fiddle, flute, accordion, guitar, banjo, concertina, harmonica, fife, piccolo, cornet, and other instruments used to provide dance music and amateur entertainment. The tutors can often provide insight into instrumental technique of the times. Such books also typically contain many tunes to test one's newly acquired skills. Separately published books of tunes designed to be played on various instruments provide valuable documentation of repertory and the changes in musical style and taste through time. The Center owns more than four hundred instrumental tutors and tune books from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Trade Catalogs

Manufacturers' catalogs for instruments, printed music, and phonograph records have long been important primary sounces for researchers. We have established a separate collection of trade catalogs that includes both older items purchased on the rare-book market and newer items obtained from current businesses. Also included are microfilm copies of phonograph-record catalogs from Columbia, Edison, and Victor held by the Library of Congress.

Posters, Programs, and Playbills

Items that document live performances in theaters and clubs are valuable primary sources. The Center maintains such materials in a separate collection, which includes many playbills from the nineteenth century and is especially strong in blackface-minstrel items.

Music Manuscripts

The commonplace books or copybooks in which musicians have written down either their favorite pieces or tunes that they needed help in remembering are unique documents that provide extremely valuable insights into popular repertory. The Center has acquired more than two dozen such items, most from the early nineteenth century. Both instrumental music—such as fiddle and fife tunes—and vocal music are represented in these manuscripts.

Sacred Tunebooks and Gospel Songbooks

The library of Milton Grafrath forms the basis for the Center's print holdings in vernacular religious music. This library of approximately twenty-six hundred volumes includes nineteenth-century oblong tunebooks, Sunday-school books, gospel songbooks from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, text-only hymnals, and many modern denominational hymn books. Considerable material has been added to this core collection, particularly in the area of southern shape-note books—both the older four-shape oblong books and the more modern seven-shape gospel songbooks. The Center holds one of the largest institutional collections of southern gospel songbooks, from publishers such as James D. Vaughan, Stamps-Baxter, and Ruebush-Kieffer. Numerous songbooks from the African American gospel tradition have been added as well.

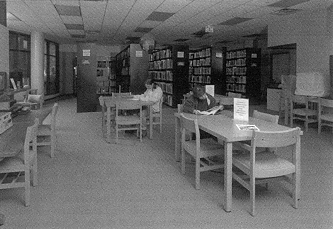

After several years in the cramped, makeshift

quarters in the LRC, the Center moved in spring 1992 into its permanent

home in the newly constructed John Bragg Mass Communication Building.

The new location features increased space for researchers and staff, climate-controlled

storage for archival materials, and a fully equipped audio restoration

lab. In addition to the director and secretary, the Center's staff

includes three full-time professionals, two permanent part-time paraprofessionals,

and two to five student assistants.

The Center's collections are open to anyone doing relevant research.

Users range from local school children to writers and scholars from foreign

countries. People from nearly every state in the country have utilized

the Center's resources. No materials circulate, but general-collection

books and most periodicals are kept on open shelves in the reading room

and are available to patrons on a self-serve basis. Other materials

are kept in closed stacks and are retrieved by Center staff. General-collection

books and several thousand published sound recordings are cataloged in

OCLC. The sheet music (including song broadsides), rare books, trade

catalogs, unpublished audio and video recordings, posters, programs, and

playbills are cataloged in-house using InMagic database software.

A project to continue the cataloging of published sound recordings in InMagic

databases is currently underway. Some of these databases are available

for searching via the Center's homepage on the World Wide Web.

Special reference resources (all on microfilm)

include copies of the Catalog of Copyright Entries of Musical Compositions

from 1891-1946; the Freeman (Indianapolis, 1890-1916), a black entertainment

newspaper comparable to Variety; over four hundred dissertations on a broad

range of topics in American music; and the Dictionary of American Hymnology,

a first-line index to over one million hymns.

For more information on the Center for Popular Music,

write to Box 41, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN 37132,

or visit the Center's homepage at http://popmusic.mtsu.edu/.